The FAA has come under pressure as of late to further figure out proper enforcement for UAS operations. Understandably they do not have the funding to staff an Aircraft Safety Inspector (ASI) on every street corner nor do they have tracking mechanisms like UTM and Remote ID in place. As a result, they have turned to local law enforcement to be their eyes and ears in the field – despite that local law enforcement are unable to enforce federal aviation regulations. This leaves the FAA in a precarious position where they need to train local officers on what they can and cannot do to be a partnering resource.

While the FAA has put out a couple of memos to local law enforcement previously there has been a call for them to give greater detail on what law enforcement should and should not do in responding to a perceived UAS violation. Yesterday the FAA put forward their latest effort – The Public Safety Drone Playbook. This new multi-page flier is a visually appealing document with lots of wonderful graphics. Unfortunately, the text of the document has some serious failings. Where this playbook is supposed to clarify UAS regulations, it both oversimplifies and provides completely inaccurate information that neither helps police, the drone community, or the FAA in several ways.

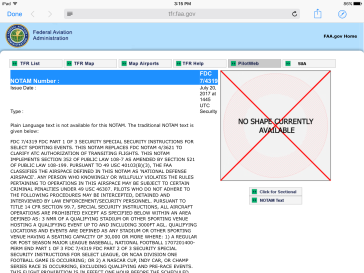

To start, the FAA attempts to inform officers of the stadium TFR. It fails miserably in doing so. The directions offer up that the “FAA issues Temporary Flight Restrictions” “at stadiums hosting large sporting events.” If you are not familiar with the world of aviation you’d be led to believe that aircraft and drones would not be allowed to fly at Denver’s mile high stadium for an NFL preseason game or at the Michigan State University Green and White game. After all, both stadiums have capacities of over 70,000 and these are large sporting events given that attendance is quite high for each. But as they are not regular or post-season games, the TFR does not apply. The playbook also doesn’t distinguish the type of sporting event.

When the National Hockey League has an event at Wrigley field in Chicago, the stadium TFR also does not apply as it doesn’t extend to NHL games even if the stadium is filled to capacity. This can lead to awkward encounters with UAS operators being confronted about restrictions that just don’t exist – encounters that can be liability concerns for the local police departments.

Similarly, the playbook is advising law enforcement to demand view of the operator’s Certificate of Authorization (COA) and provides a sample COA document. Of course, the vast majority of legal UAS operations within controlled airspace don’t have a COA document establishing the validity of the flight. Rather with the LAANC system, drone operators submit for airspace authorizations and receive SMS text replies with authorization codes that give them permission to fly within the specific area at the specific time. This documentation gives a false sense to an officer that a COA as expressed in the playbook is required.

But the most major gaffe in this playbook document comes in their overview of “What is my authority?” portion of the materials. Here the FAA recognizes that local law enforcement are partners but lack the ability to enforce federal aviation regulations. As a work around the FAA attempts to suggest measures that local law enforcement agencies can use to police suspected rogue UAS operations. They correctly offer that LEOs can ask to see the proof of aircraft registration and any waiver for the drone’s operation. These items are standard FAA ramp check details. UAS registration is required as it was signed into law on December 12th, 2018 after previously having been tossed out by the federal courts in the Taylor v. FAA case in early 2018. An officer can inspect the drone for external registration markings and get assurance that the drone is registered by seeing the proof of aircraft registration – a card printed out from the FAA DroneZone upon successful UAS registration. Likewise, any waiver (which includes the affixed application for waiver) can also be reviewed to ensure that the UAS flight has proper authorization from the FAA. But immediately after stating these two “CAN” options, the FAA puts forth, “While law enforcement can ask, a UAS or drone pilot is NOT required by federal regulation to make their UAS FAA Remote Pilot Certificate available.” Wait! What?!?!? This statement by the FAA is complete and utter hogwash and completely throws out their two previous “CAN” request statements. Here’s why…

The FAA stating that a UAS operator is not required to show their FAA Remote Pilot Certificate goes against §107.7(a)(1) which requires the Remote Pilot in Command (RPIC) to make their remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating available to the Administrator.

According to 14 CFR §1.1 the definition of an Administor is “the Federal Aviation Administrator or any person to whom he has delegated his authority in the matter concerned.”

This becomes key in also mandating that the RPIC show proof of their registration and waiver documentation. If the FAA is contending (as they did with their statement on not requiring an RPIC to show their certification) that local police do not meet with the 14 CFR §1.1 definition of Administrator, then operators are also NOT required to show registration or waiver proof as those items are defined in §107.7(a)(2). You can’t have one without the other.

Inevitably though even getting to the point of officer intervention there is the challenge of suspecting a criminal action is taking place. Just as “stop and frisk” was found to be unconstitutional, a police office needs to have some reasonable suspicion that the operation is not within legal boundaries in order to detain and require the production of documents to prove the legality of the operation. That poses a great challenge where law enforcement need to know whether or not the airspace at the location is controlled airspace, have a keen eye to really figuring out if the drone is at 410’ AGL of 350’ AGL, and being able to determine whether the flyer is a hobbyists and fully allowed to fly at night with no waiver or a Part 107 RPIC that requires one. The best first response then of any drone operator to a police office that has approached them with questions is probably, “am I being detained?” – and that isn’t the most desired way to start an interaction.